Are viral TikTok trends making it worse?

BBC

BBC“Stop them!” I shouted as I sped through London’s Finsbury Park station in my electric wheelchair. I was surrounded by passengers. Nobody intervened.

I was traveling alone and was checking my route home at a crossing when suddenly I felt someone coming towards me.

I looked up to find a man standing a few inches from my face, staring at me. He was motionless and looked me dead in the eye. I froze; I thought I was going to be attacked.

The man grinned, stuck out his tongue, and wore a blank expression. Then I noticed someone pulling me from behind. As I turned in my wheelchair, most of the group joined them through the turnstiles.

Angrily, I chased after him, hoping they would delete the video. But just as I approached, the men ran up the stairs, laughing. That was the last time I saw them.

I was the latest victim of the “tongue-sticking” TikTok prank, in which people stick out their tongues at strangers and film their reactions – but this time I went perverted to mock me for my disability.

The situation looks familiar. A year ago I wrote about confronting TikTok-inspired disability harassment from school children shouting “Timmy” at me outside my local train station.

This was a reference to a disabled character from the satirical series South Park who uses a wheelchair and can only shout his own name loudly and uncontrollably. Revitalized on TikTok decades later and stripped of its comedic context, imitating Timmy has again become a way to make fun of people with disabilities.

That time I chose to address the children directly during the conversation; I was hoping this could be a learning experience that would break down their preconceptions.

This time I took action at Finsbury Park.

Tired of feeling powerless, I immediately reported the incident as a hate crime; this offense is now defined by law in the UK to include acts of perceived hostility towards protected characteristics such as disability.

British Transport Police (BTP) confirmed that my experience was similar to a number of other incidents that appear to have been fueled by the TikTok craze.

The targeting of people themselves by those seeking online influence is an area of ”increasing concern”, according to Ciaran O’Connor of the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD), a think tank focusing on online hate.

He says social media algorithms prioritize “shock, confrontation, and hostile encounters” — or, as many of us know it, the “anger trap” — over empathy.

Online hate ‘going viral’

The original TikTok joke copied by the guys who targeted me isn’t as bad as you might expect. It was popularized by US teen influencers such as Pink Cardigan, who garnered millions of likes this summer by sticking her tongue out at confused shoppers in stores. and restaurant windows.

Aidan Walker, whose videos about internet culture have garnered millions of views on TikTok, explains that comedy depends on the reactions of people who are “not in on the joke.” He says that, like many of its kind, the tendency to stick out its tongue began as something “obnoxious and inconsiderate rather than inherently hostile.”

When I was harassed, adult men, ostensibly in their early 20s, chose to use this trend to make fun of disability—perhaps to differentiate their attribution. Mr. O’Connor adds that they were probably “performing with the intention of going viral.”

I have yet to find footage of my incident uploaded to TikTok or other social media platforms, but that doesn’t rule out possible intent.

TikTok says the vast majority of content uploaded on the trend is not targeted or hateful and therefore does not violate its policies.

The platform’s community guidelines prohibit hate speech, hateful conduct, or promotion of hateful ideologies, including discrimination based on disability.

When BBC News reported on video of teenagers targeting a man with Down syndrome by sticking out his tongue outside his window, moderators removed the video.

Reluctance to report

Mr. O’Connor says viral trends are being distorted to also target other minority groups, including LGBTQ+ individuals and immigrants, and that content creators are motivated by an endless quest for inclusion.

Ministry of Internal Affairs statistics In England and Wales, hate crimes driven by racist and religious offenses appear to have continued to rise this year.

While recorded disability hate crimes are set to fall by 8% in 2025, this follows sharp rises in recent years and disability charities are warning of a distorted picture.

Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) Last year’s hate crime against disabled people was explained as one of the “most common and underreported” forms of discrimination.

The marked decline in reports of disabled hate crime reflects “a lack of trust in reporting, not a decline in hostility”, said Ali Gunn of disability charity United Response.

charity’s research shows Only 29.9% of people with disabilities report crimes against themselves; Only 2% of public order crimes result in conviction; this is the lowest rate among all minority groups.

I experienced these challenges firsthand when reporting my incident. Despite the definition of disability hate crime covering a wide range of perceived hostile acts well beyond verbal abuse, I was initially told that the case would not be pursued as there would be no audio on the CCTV and no obstructive or derogatory language was used.

I pushed back, emphasizing that being surrounded in my wheelchair was intended intimidation and asked if the CCTV had been reviewed. Only then was my case reopened and handled by another officer.

The footage was then analyzed and photos of the suspects were forwarded to BTP’s investigation team.

TfL apologized for the incident and the way BTP initially handled it. TfL commissioner Andy Lord wrote to me to express his disgust at the abuse I had faced and to confirm TfL’s commitment to improving reporting and awareness of disability hate crimes.

Journey to change?

It is clear that it is necessary to combat hate crimes in and around public transportation. TfL data shows that overall hate crime reports across its services increased by 39.7% between 2022/23 and 2024/25, with a slight decrease between 2023/24 and 2024/25.

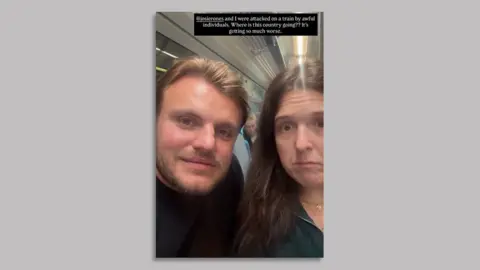

Last month, comedian Rosie Jones, who has cerebral palsy, had wine thrown on her. “Enableist and homophobic attack” He’s returning home by train after a concert with his comedian friend Lee Peart.

“They mocked our voices, insulted us, and even threw a wine bottle (thankfully plastic) at us,” Jones wrote in an Instagram post. “This was a stark reminder that my cerebral palsy makes me stand out and is often used as a weapon against me.”

What sticks with me from my experience at Finsbury Park, perhaps more than the shooting itself, is how passers-by failed to intervene.

This made me realize that bystanders can feel incredibly conflicted about taking action.

What lies at his heart is this hesitation to take a step. TfL’s new Act Like a Friend campaignThis encourages passengers to chat with the targeted person and act as if they know each other.

@itsleepeart

@itsleepeartThe network encourages customers to report to the police any incidents they believe are motivated by hatred or hostility, including the making of hate films.

“Everyone deserves to be safe and feel safe when traveling on our network,” says Siwan Hayward, TfL’s enforcement manager for policing. “The behavior Alex describes is deplorable.”

United Response’s Gunn said making hate films was a growing and deeply distressing trend for disabled people.

He called on social media companies to “reinforce moderation” in the face of viral challenges by improving systems for victims or advocates to flag harmful content.

This includes not only removing offensive content, but also making users who post that content face tougher sanctions.

“Being mocked or secretly filmed tarnishes people’s dignity and reinforces the message that public spaces are not safe or welcoming,” he says. “These incidents sit alongside more overt forms of disability hate crime and share the same fundamental problem of hostility and exclusion.”

Four months after what happened, I was pretty depressed. While I’m glad I took action when I could, the harassment I’ve experienced in recent years has made me aware that the fight is now taking place on two fronts – online and in the real world.

So what to do? Clearly, bigger picture change is needed to combat hate in both areas. But on an individual level, beyond screens, nothing is more powerful than looking out for each other. Hate thrives on invisibility.