Inside the quest for the origin of Stonehenge’s Altar Stone

“It was one of those kind of serendipitous events; it was a Eureka moment,” says Professor Richard Bevins.

Choosing a set of 15 sample stones from Stonehenge given to him by a former colleague, the experienced geologist was asked to make a quick observation about the source of the rock, thought to have been brought from West Wales around 5,000 years ago.

“I said I could tell you what they were in terms of rock type, but I had never seen that type of rock in West Wales, never seen it,” Prof Bevins recalls. “That’s why I wrote [his report]but before it was published I had a Eureka moment and thought ‘there’s an outcrop that I’ve gotten the material from but I’ve never looked at before’.

“It led to the excavation of a Neolithic quarry [Craig Rhos-y-Felin] and discovering the exact location where the stone samples came from. A perfect match. “It was a special moment.”

This major discovery in 2011 was the first time a definitive provenance had been found for any stone from the world-famous monument and revived the long-running debate about how the stones were transported from Pembrokeshire to Wiltshire.

Today, 14 years later, Prof Bevins believes he may be on the verge of his next breakthrough discovery; source of the monument’s Altar Stone.

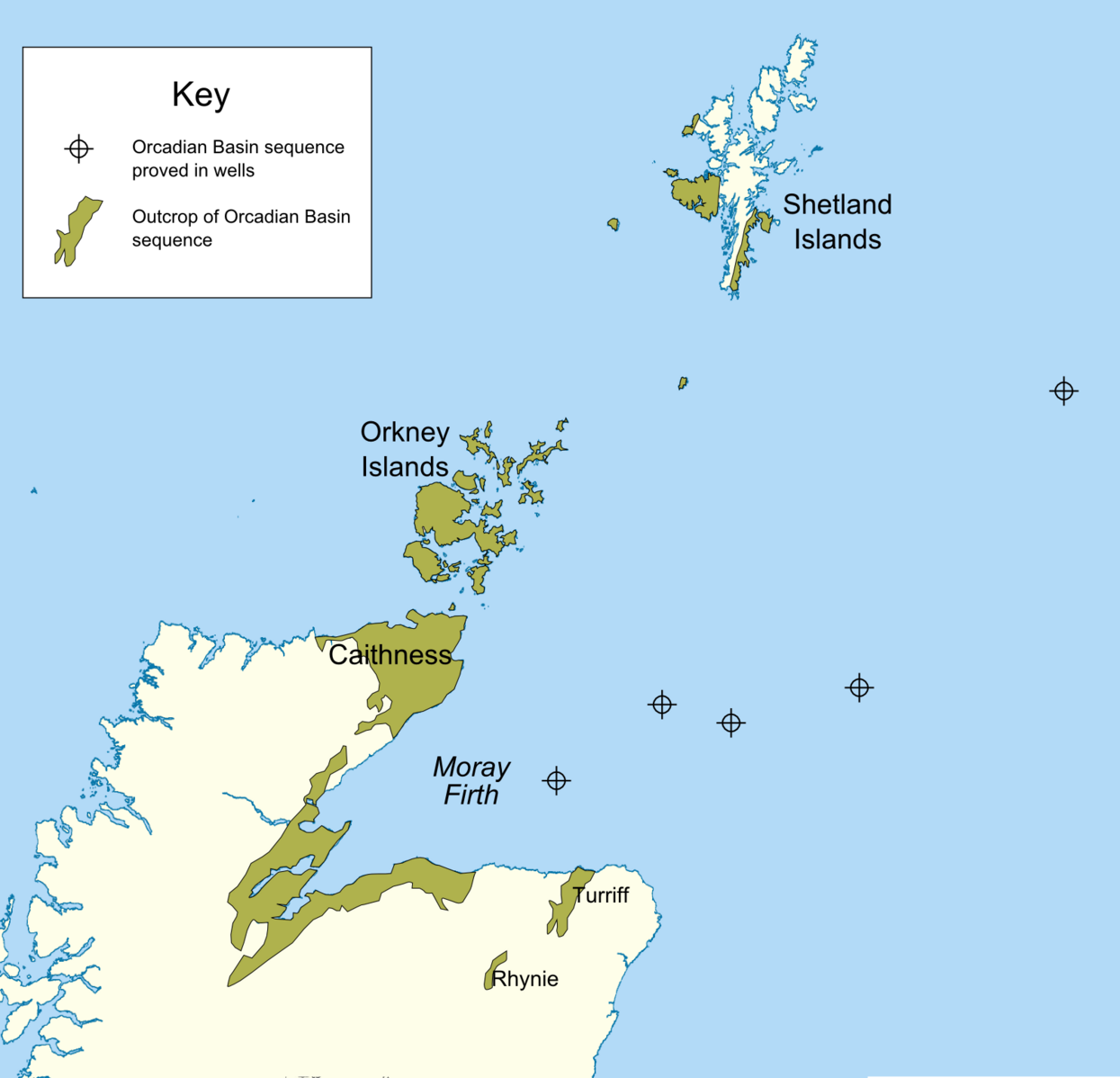

Declaring that the six-tonne megalith was not one of the bluestones brought from Pembrokeshire last year, he and his team traveled to the Orkney archipelago after determining that it came from sandstone deposits in the Orcadian Basin, which covers the islands of Orkney and Shetland and a coastline on the north-eastern Scottish mainland.

But detailed study of the stones in Orkney yielded no results – and now Prof Bevins is looking at a 125-mile x 93-mile mapped area, determined to discover the exact location where the stone was quarried before being transported more than 500 miles away to the West Country.

“It would be great to find the exact source,” says Prof Bevins. “It’s been a roller-coaster for me to get to this point when I found out he wasn’t from Wales, but now northeast Scotland. It would definitely be the icing on the cake on top of all the work we’ve done.”

Finding the resource will trigger excavation work for archaeologists at the resource site, who will then be able to trace the people behind Stonehenge’s construction and learn about everything from their society to their tools to what they ate and drank.

Professor Bevins also says it would add further substance to theories behind how the huge stones were transported hundreds of kilometers away due to the rugged terrain in Scotland, instead being transported by sea.

.jpeg)

The discovery of the location could also bolster research that the construction of Stonehenge was a UK-wide act of unification against a foreign threat, with materials from all corners of the British Isles.

But for now, Prof Bevins says he needs to work with his small team to identify sites in the huge region.

“If we went up there and randomly walked around the whole area, we would probably retire and be underground for a long time before anything was found, so we would pick some target areas in that area,” says Prof Bevins.

However, this takes time and working in the field is expensive and time consuming.

After funding for the Orkney decommissioning ran out last year, Prof Bevins and his team need to raise a new coffer to pay for the next part of their project. Some of this will be driven by the public’s thirst to learn about Stonehenge, one of the UK’s most famous monuments, with a record-breaking 1.4 million visitors in 2024.

“People like to learn about other people, they like to know their history, they like to know why Stonehenge was built, what the pyramids mean. It’s a fascination with people and cultures,” says Prof Bevins.

“When we publish an article [on Stonehenge] You can measure time by traveling across time zones almost anywhere in the world. News, television channels, online. It’s really quite surprising. “We hope to achieve the same results again soon.”