Mekedatu dam project: a long-standing source of friction between Tamil Nadu and Karnataka

The Mekedatu dam project returned to the agenda of the Supreme Court on November 13, 2025, which gave its approval for consideration of the Detailed Project Report (DPR) prepared by the Cauvery Water Management Authority (CWMA) and the Central Water Commission (CWC).

The idea of the project proponent – the Karnataka government – is to seize 67.16 thousand million ft3 (TMC) of water by building a ₹ 9,000-crore balancing reservoir at Mekedatu (meaning ‘goat’s leap’ in Kannada), about 100 km from Bengaluru. The project will also include a 400 MW (megawatt) hydroelectric component. In the Supreme Court’s 2018 verdict on the Cauvery dispute, an additional 4.75 TMC was sanctioned on Karnataka.

arguments

In the case before the court in Karnataka, it was revealed that what the State wanted to do was “use only the water allocated to it as per the CWDT Order”. [Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal]as amended by this court. The upper riparian state also argued that it was “entirely within its right” to use its allotted water. in the best way possible. Even after the construction of Mekedatu dam, the uncontrolled flow of water towards Tamil Nadu and the Union Territory of Puducherry would not be affected.

Claiming that Karnataka does not have the right to build a dam in Mekedatu, Tamil Nadu claimed that if the proposed dam is allowed, “the right to uncontrolled water flow will be adversely affected”. By building dams “Karnataka, ActuallyTo do anything which, in the opinion of the lower riparian State, would amount to a modification of the Decision made by the CWDT as modified by this court.

Hearing both the sides, the Supreme Court declared that Karnataka will have to release the water to be metered by CWC at Biligundulu gauging point as directed by CWMA. Furthermore, “each State is free to use the water allocated to its quota in such manner as it deems most in the interest of the State. No other State has the right to interfere with the decision regarding the management and use of water allocated to a particular State unless the water allocated to that State is reduced by such action.”

‘Revised’ DPR

It is against this backdrop that the Karnataka government has decided to give new life to the project by planning to submit a “revised” DPR to the Central authorities soon. Looking at the history of the Cauvery dispute, the Mekedatu project has cropped up several times during inter-state negotiations as well as talks between all the Cauvery basin states, including Kerala and Puducherry.

Review of existing materials Hindu Archives It reveals how the project has been hotly debated for 75 years. As early as February 1950, this newspaper reported that the two governments had reached an agreement and that the former had received a revised draft agreement from the latter, with the latter “securing” the other State’s approval for the power generation of Mysore, also known as Mysore, just as Tamil Nadu was then called Madras. In 1950, the project, which initially envisaged generation of 15 MW and eventually 35-40 MW, was estimated to cost ₹ 5 crore, of which the first phase itself would cost ₹ 3.5 crore.

Kamaraj period

Between 1962 and 1964, detailed studies were carried out for the establishment of two dams and two power plants near Hogenakkal at a total cost of ₹ 80 crore, which could generate 800 MW of electricity. The plan included the construction of a 470 ft high dam and a large power station at Rasimanal, 15 km upriver (also in Tamil Nadu).

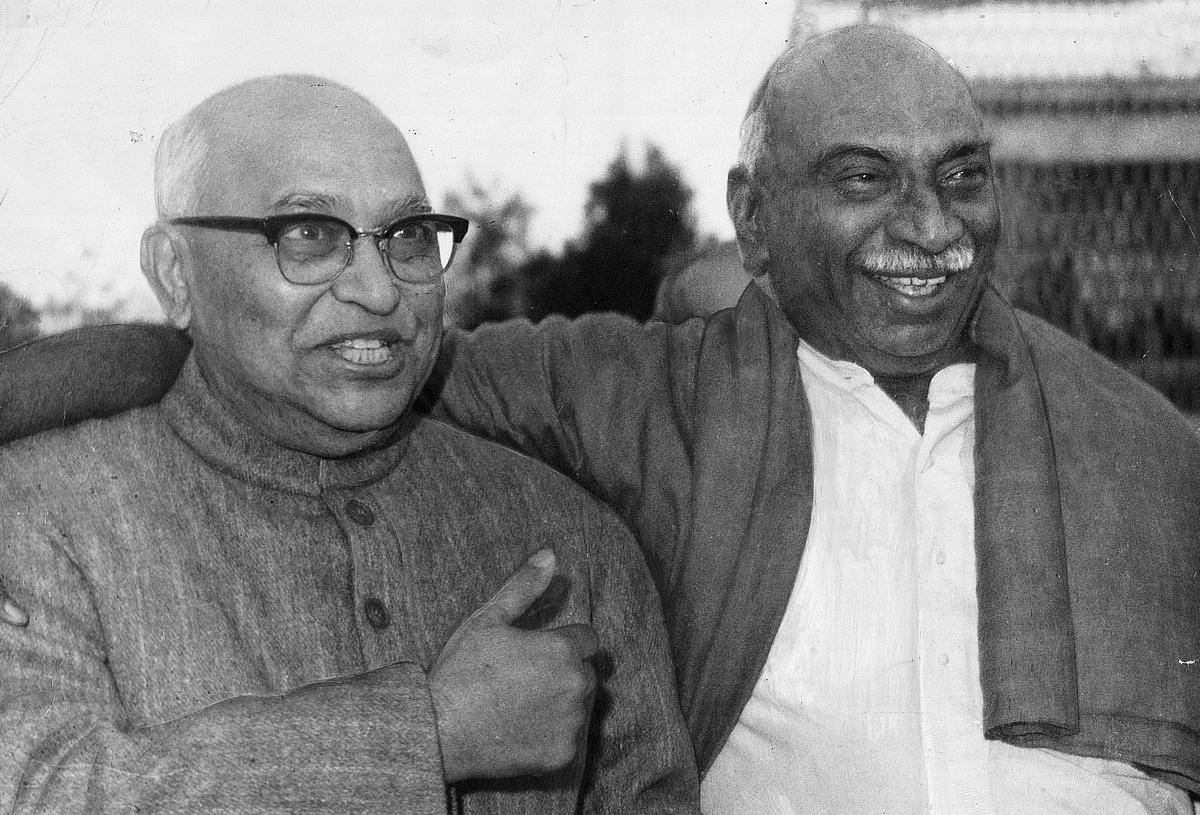

S. Nijalingappa (left) and K. Kamaraj (right) in 1967 | Photo Credit: Hindu Archives

Talking about investigative work, R. Sengottaiyan, former Chief Engineer of the now defunct Tamil Nadu Electricity Board, which was in charge of hydroelectric projects, reminded this correspondent in the 1990s that in February 1963, Chief Ministers of the two States, K. Kamaraj and S. Nijalingappa, had planned to visit the site of the proposed Hogenakkal hydroelectric project with the expectation that even the foundation stone would be laid then. However, the former engineer said the visit was postponed at the last minute and never took place.

Committee

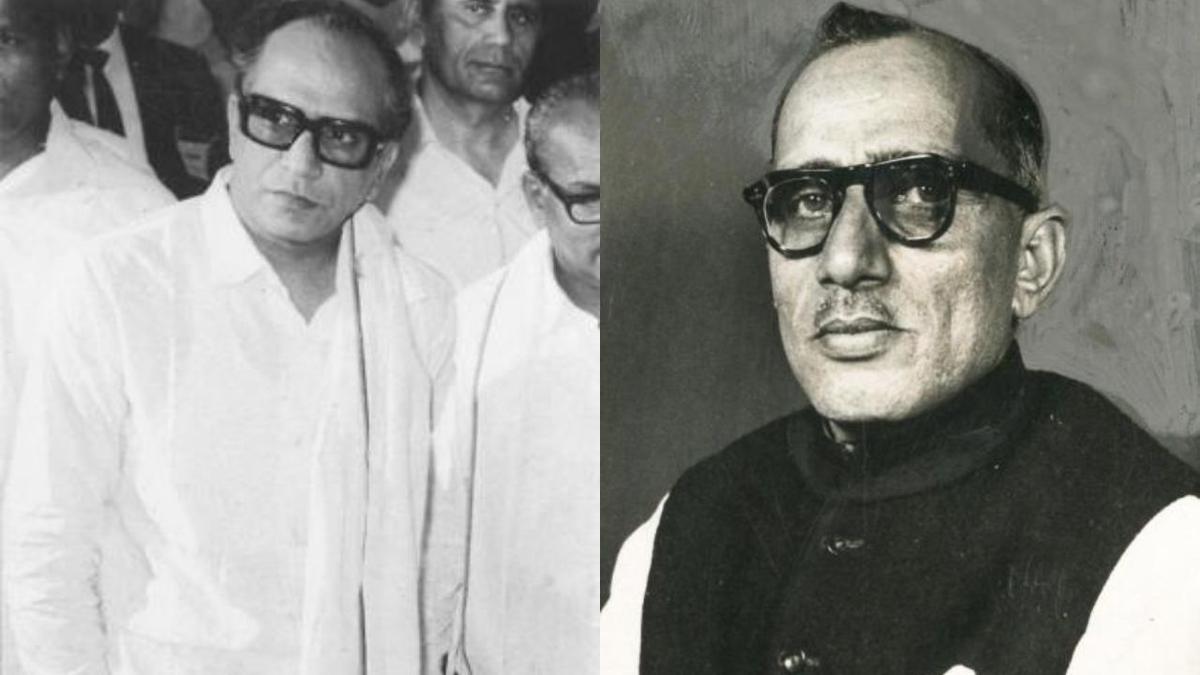

According to a report published by , when the Irrigation Ministers of the two States – HM Chennabasappa and PU Shanmugam – met at the picturesque spot of Hogenakkal on June 5, 1974, an agreement was reached that the officials of the two States would independently survey and also hold mutual consultations to carry out detailed feasibility studies of power projects. Hindu the next day.

PU Shanmugam (left) and HM Chennabasappa (right) | Photo Credit: Hindu Archives

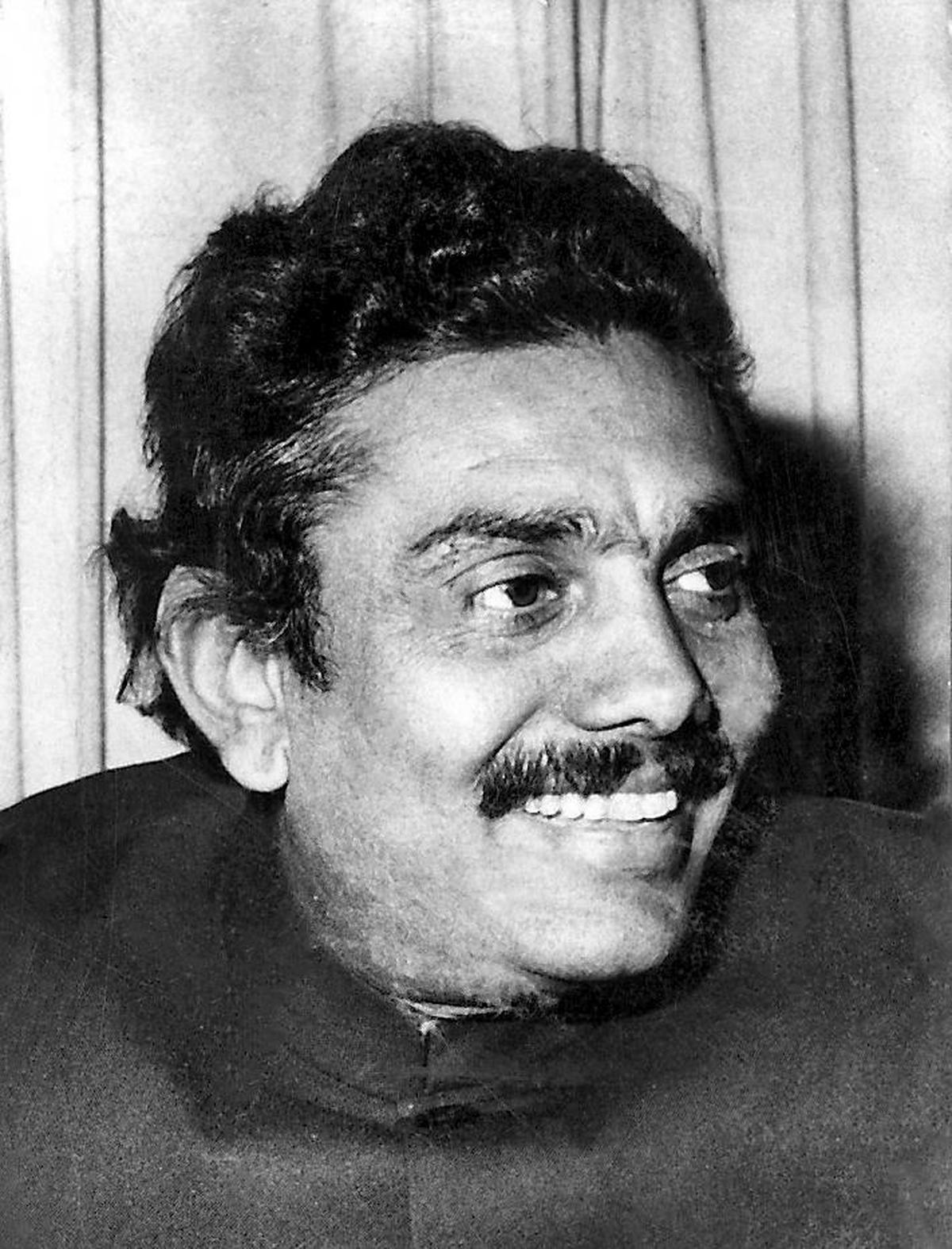

According to a report of this newspaper dated November 12, 1980, in November 1980, the then Karnataka Chief Minister R. Gundu Rao, in a press conference, said that his government had formed a nine-member committee to prepare a feasibility report on the Mekedatu project envisaging power generation of about 1,000 MW.

A year later, he claimed, the expert panel concluded that the Mekadatu hydroelectric project was more suitable for construction than the Hogenakkal project proposed by Tamil Nadu. However, in February 1987, the then Minister for Industries and Power, JH Patel, took a conciliatory tone towards Tamil Nadu when he said that his State had suggested to both the Center and Tamil Nadu that the Mekedatu and Hogenakkal projects be treated as joint projects without raising the Cauvery waters dispute, but there was no response from the two governments. Patel, who was a Minister in the Janata government headed by Ramakrishna Hegde, informed the Parliament that his State had sought permission from the Center for Mekedatu.

R. Gundu Rao | Photo Credit: Hindu Archives

The Mekedatu dam project came up for discussion between August 1996 and January 1997, when the two States held five rounds of talks to resolve the core Cauvery dispute in the light of the Supreme Court recommendation. According to a report prepared by senior journalist of Karnataka PA Ramaiah and published in this diary on October 27, 1996, the Center was inclined to take up the Mekedatu project as its own. The cost could be ₹ 2,000 crore and the power (about 950 MW) could be shared by the four riparian States. Mekedatu was not seen as an alternative to Tamil Nadu’s Hogenakkal project.

Karunanidhi era

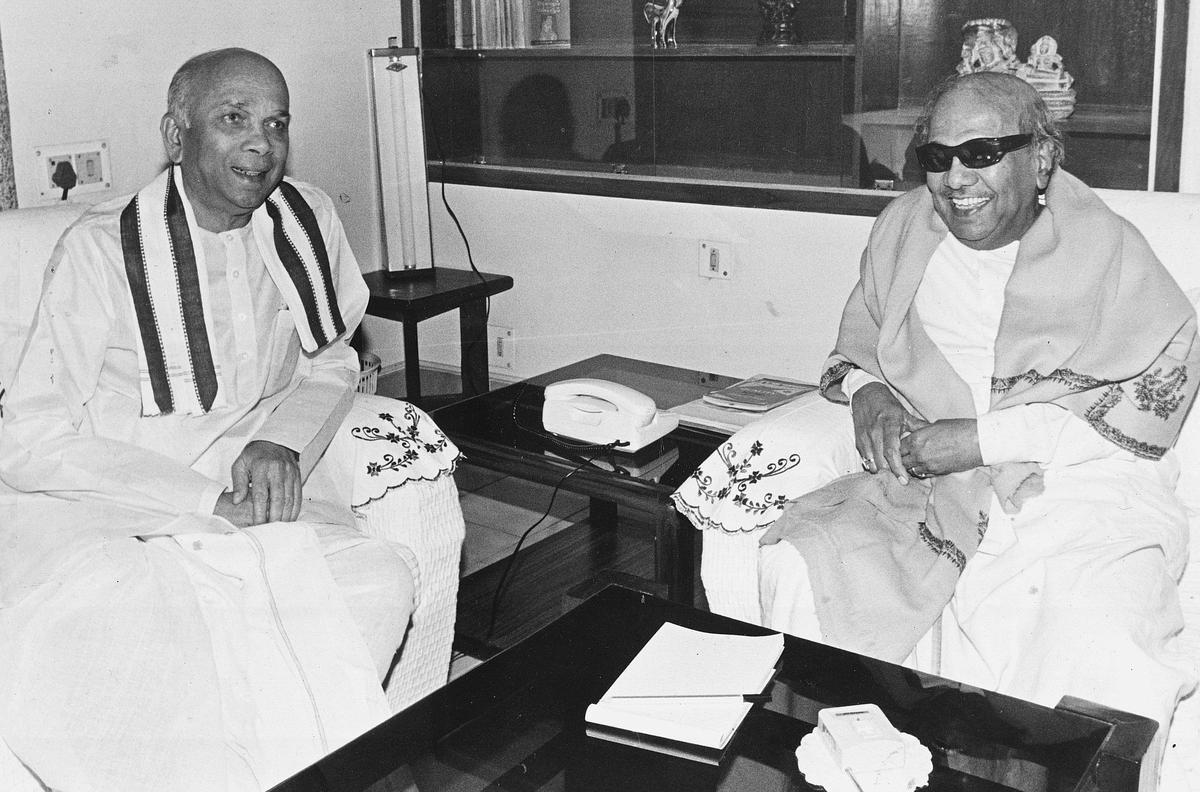

Two weeks after the fifth and final round of talks held in Chennai on January 5, 1997, the then Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi told reporters that it was the Mekedatu project that stood in the way of reaching an agreement on sharing of Cauvery water between the two States. However, when his Karnataka counterpart Patel returned to Bengaluru on the same day he led his state’s talks with Tamil Nadu, he told reporters that the reason the talks had failed was because Tamil Nadu was demanding a higher share of the river water.

JH Patel (left) and M. Karunanidhi (right) in 1997 | Photo Credit: Hindu Archives

While PR Kumaramangalam was the Union Power Minister in the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP)-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) regime between 1998 and 2000, he made efforts through the National Hydro Power Corporation (NHPC) to revive the Mekedatu and Hogenakkal project as components of a larger hydro power scheme that also included power plants at Shivasamudram and Rasimal. Aiming to meet the total demand of 1,150 megawatts (MW), the Cauvery Hydro Power Project (CHPP) envisaged setting up four power plants at Shivasamudram (270 MW) and Mekadatu (400 MW) in Karnataka and Rasimanal (360 MW) and Hogenakkal (120 MW) in Tamil Nadu.

PR Kumaramangalam in 1999 | Photo Credit: Hindu Archives

Discussions initiated in 1999 continued for years at different levels, facilitated by the Centre. In August 2008, emerging from a nearly hour-long meeting with Prime Minister M. Karunanidhi at the Secretariat, Union Minister of State for Energy, Commerce and Industry Jairam Ramesh explained the rationale behind pursuing the “difficult” project. He explained that the cost of electricity through CHPP would be ₹2.5 to ₹3 per unit, at a time when the US was purchasing electricity at a rate of ₹7.5 to ₹8 per unit. Finally, after a tour in Chennai in August 2009, the talks failed. The basin states were unable to reach any agreement for one reason or another.

Jairam Ramesh in 2008 | Photo Credit: Nagara Gopal

Over the last 10 years, especially following the 2007 final judgment delivered by the Court, the approach of the upper riparian State has been to present the Mekedatu project as a project aimed at implementing the final judgment, as amended by the Supreme Court in 2018. Moreover, the aim of the project is to address the drinking water supply requirements of Bengaluru, some of which were accepted by the Court.

Tamil Nadu’s position was that the Authority and the CWC should not consider its neighbour’s Mekedatu request, given the upper riparian State’s “track record” in implementing the Court’s orders. However, the battle over Mekedatu is likely to intensify further after the Court gave its nod for consideration of the revised DPR, which Karnataka is expected to file in the coming months.