Over a third of animals lost in test deep sea mining

Georgina RannardClimate and science reporter

Natural History Museum / University of Gothenburg

Natural History Museum / University of GothenburgScientists, who conducted the largest research of its kind, revealed that mining machines in the deep ocean cause serious damage to life on the seabed.

They found that the number of animals found in vehicle tracks decreased by 37% compared to untouched areas.

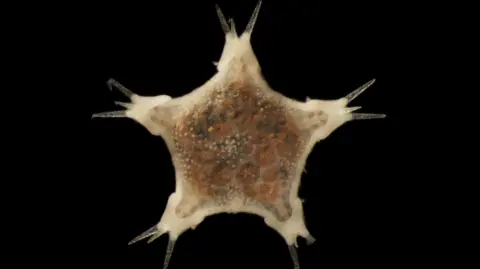

Researchers have found more than 4,000 animals, 90% of which are new species, living on the seafloor in a remote part of the Pacific Ocean.

Vast amounts of critical minerals needed for green technologies may be locked deep in the ocean, but deep-sea mining in international waters is highly controversial and is not currently permitted until more is known about its environmental impacts.

Natural History Museum / University of Gothenburg

Natural History Museum / University of GothenburgThe research, by scientists at the Natural History Museum in London, the UK’s National Oceanography Center and the University of Gothenburg, was carried out at the request of deep-sea mining company The Metals Company.

The scientists said their work was independent and the company could see the results before they were published but was not allowed to change them.

The team compared biodiversity two years before and two months after test mining, which took the machines 80 km across the seafloor.

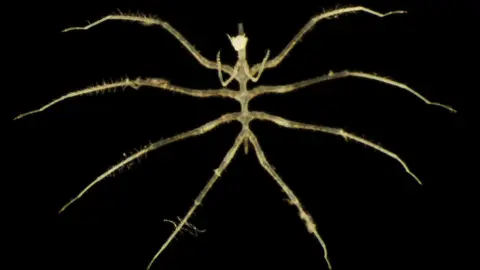

They specifically examined animals between 0.3 mm and 2 cm in size, such as worms, sea spiders, snails and oysters.

The number of animals in the vehicle’s tracks decreased by 37 percent and species diversity by 32 percent.

Lead author Eva Stewart, a PhD student at the Natural History Museum and the University of Southampton, told BBC News: “The machine removes about five centimeters of the sediment. Most of the animals live there. So if you’re removing the sediment, you’re removing the animals in it.”

Natural History Museum/University of Gothenburg

Natural History Museum/University of Gothenburg“Even if they are not killed by machinery, pollution from mining activities can slowly kill some less resilient species,” said Dr Guadalupe Bribiesca-Contreras of the National Oceanography Centre.

A few of the animals may have moved away, but “whether they returned after the disturbance is a different question,” he added.

However, animal abundance did not decrease in areas where sediment clouds descended near vehicle roads.

“We were probably expecting a little bit more impact, but [we didn’t] Dr. D., a research scientist at the Natural History Museum. “We’re seeing a lot, it’s just a shift in which species are dominant over others,” Adrian Glover told BBC News.

Natural History Museum/University of Gothenburg

Natural History Museum/University of Gothenburg“We are encouraged by this data,” a spokesman for The Metals Company told BBC News.

“Following years of alarm from activists that our impacts would extend thousands of kilometers beyond the mine site, the data shows that any impacts on biodiversity are directly limited to the mined area,” they added.

However, some experts think this is not good news for mining companies.

Dr. D., a senior research fellow at think tank Chatham House’s Center for Environment and Society. “I think this study shows that current harvesting technologies are too damaging to allow large-scale commercial research,” Patrick Schröder told BBC News.

“These were just experiments and the impact was significant. If they did it on a large scale, it would be even more harmful,” he added.

Deep sea mining is controversial. At the center of the debate is a difficult problem.

The latest research was conducted in the Clarion-Clipperton Region, a 6 million square kilometer area in the Pacific Ocean estimated to contain more than 21 billion tonnes of nickel, cobalt and copper-rich polymetallic nodules.

The world needs these critical minerals for renewable energy technologies to combat climate change. For example, solar panels are key components in wind turbines and electric vehicles.

The International Energy Agency predicts: Demand for minerals could at least double by 2040.

Minerals have to come from somewhere, but some scientists and environmental groups are seriously concerned that deep-sea mining could cause untold damage.

Natural History Museum/University of Gothenburg

Natural History Museum/University of GothenburgSome fear that life may be endangered before we have a chance to discover the full nature of life in the unexplored deep ocean.

Oceans play a critical role in regulating our planet and are currently at serious risk from rising temperatures.

The International Seabed Authority (ISA), which governs activities in international waters, has not yet approved commercial mining, although it has issued 31 exploration licences.

A total of 37 countries, including the UK and France, support a temporary ban on mining.

This week Norway postponed mining plans in its waters, including the Arctic.

However, in April, US President Donald Trump called for the acceleration of domestic and international projects because the US wanted to secure the supply of minerals to be used in weapons.

If the ISA concludes that current mining techniques are too destructive, companies could seek to develop less invasive ways of extracting nodules from the seafloor.

The research was published in the scientific journal Nature Ecology and Evolution.