Mexico reassesses Malinche: From traitor to victim

MEXICO CITY — It has been denigrated for centuries; Her name, Malinche, was synonymous with deception and Native collaboration with Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, for whom she served as translator, advisor, and mistress.

Mexican Nobel Prize-winning author Octavio Paz accused Malinche of being a kind of malevolent Eve whose subservience to Cortés had forever tainted Mexico’s composite identity.

In the 1980s, angry residents of the capital’s Coyoacán district forced the removal of a monument to Malinche, Cortés, and their son Martín, often referred to as the first man. crossbreed (mixed race) Mexican, but others probably preceded him.

The artist, who has long been widely admired, has been the subject of paintings, novels, films, songs, operas and TV series. The USS Malinche was a 24th-century starship in “Star Trek.”

But now Malinche is experiencing a dramatic re-evaluation; her biography is recast as a courageous feminist survival story; The saga of a young woman who uses her intelligence to succeed in a patriarchal society of rowdy and brutal Spanish conquistadors.

“I think it’s fair to say that she was the most important woman in Mexican history,” said Mexican historian Ursula Camba Ludlow, who wrote a biography of Malinche. “His decisions helped shape the face of Mexico.”

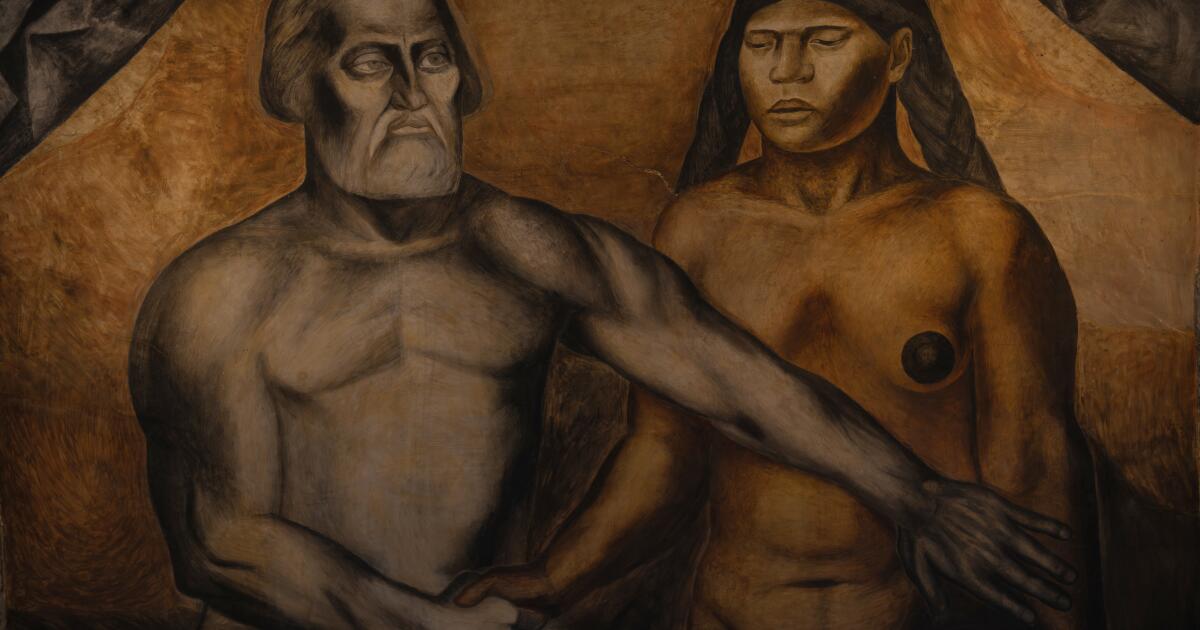

A man ascends the stairs under the “Cortes y la Malinche” mural by Jose Clemente Orozco on the ceiling above the stairs at the Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso in Mexico City.

Today Malinche is praised by Mexican intellectuals and legislators, and her image once again adorns public space in Mexico City.

Just this month, the government installed bronze statues of Malinche and five other Indigenous women along the elegant Paseo de la Reforma. This marked the culmination of a rebranding campaign spearheaded by Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum.

“Why are we putting his figure here after years when we were taught that he was a symbol of betrayal?” Sheinbaum asked during a dedication ceremony. “In fact, her life reflects the plight of an Indigenous woman immersed in a world of violence, of invasion and dispossession, forcing her to use her words and knowledge of language to survive.”

This time there was no protest, no one announced it malinchismo The behavior – which mirrored Malinche’s – marked a strange reiteration of Mexican self-hatred.

Further evidence of the paradigm shift: Theatergoers flocked to “Malinche the Musical,” the brainchild of Spanish rock star turned impresario Nacho Cano.

“Mexico has two mothers: the Virgin of Guadalupe and Malinche,” Cano said. mexican interviewer after his show moved from Madrid to Mexico City last year. “But we hid and judged La Malinche without listening to her.”

This extravaganza is a kitsch, nearly three-hour ode to a Malinche who lingers on stage in tight clothes and looks dreamily at the good-natured Cortés. Scenes of Spanish galleons and Aztec pyramids unfold amidst a pulsating tempo of rock, pop and flamenco riffs.

Monumento al Mestizaje depicts Hernan Cortes and La Malinche in Parque Xicotencatl in Mexico City. This bronze statue by artist Julian Martinez was unveiled in 1982.

The portrayal of Malinche as a brave person who supports Cortés does not seem to offend viewers, but some have condemned the work’s pro-Spanish take on the Conquest.

“I think it’s time we dropped that disrespectful word.” malinchist “To call someone a traitor to Mexico,” said cafe owner Roberto Pineda, 61, who enjoyed the performance. “La Malinche was not a bad person. On the contrary, I would say that her intelligence places her among the great women in Mexican history.”

Reinterpretations of Malinche have been going on for decades. Even as Paz disparaged her in the 1950s, some Mexican women rose up to defend her, but until recently their objections found no echo in a macho-dominated society.

The Mexican left was particularly hostile to Malinche, seeing her as the embodiment of imperialism.

Legendary Mexican activist and songwriter Gabino Palomares remains best known for “Malinche’s Curse,” a 1970s composition that is still considered a classic of Latin America’s “New Song” movement.

“Oh, Malinche’s curse!” the song ends. “The disease of our day! When will you leave my lands? When will you free my people?”

Even on the US side of the border, being called Malinche was a huge insult. However, starting in the 1960s, some Mexican Americans trying to discover their identities began to embrace it.

A couple walks past Casa Colorada in the Coyoacan neighborhood of Mexico City. Some locals attribute this historic residence to La Malinche and its association with Hernan Cortes after the Spanish conquest, but definitive historical records do not confirm this connection.

Inés Hernández-Ávila, professor emeritus of Native American Studies at UC Davis, said Malinche was “well known in the Chicana community and we loved her.” “We adopted her as our mother.”

Hernández-Ávila, the daughter of an Indigenous mother and a Mexican American father, said the narrative that Malinche was a traitor has been “debunked.” “We could see that he was being misrepresented and denied his rightful place in history.”

He recalls meeting Palomares in San Francisco after a performance of “Malinche’s Curse.”

“Why are you blaming it on him?” “Why is a woman being held responsible for all this?” he asked.

Palomares shrugged and walked away.

Who actually was Malinche? Separating myth from reality is a challenging task, but enthusiastic researchers have managed to sketch the outlines of a life.

He was born about 1500 in the Mexican state of Veracruz, on the coast of the Gulf of Mexico, probably of noble descent. Although his birthplace was not in the Aztec region, it was a region where Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs, was spoken along with regional languages. His fluency in Nahuatl would soon help shape world history.

She was probably enslaved by an ethnic Mayan group in the modern-day state of Tabasco between the ages of 8 and 15, but it is unclear whether she was kidnapped or sold. A talented linguist, he quickly mastered Mayan dialects.

In 1519, Cortés landed in Tabasco, where his forces crushed Mayan resistance. Loser cacique He offered the Spanish spoils of war: twenty young women. In a short time, they were all baptized. The Spanish did not hesitate to rape, but they wanted Christian children. Among the 20 concubines was the woman who would become known as Malinche. She was named Marina. (His birth name is unknown.)

While Cortés was looking after the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlán (now Mexico City), Marina participated in a kind of chain translation: she would translate Nahuatl into Mayan to a Spanish castaway, himself a Mayan slave, who had learned the language. He would then relay the information to Cortés. However, Marina quickly learned Spanish and became an important advisor to the Spaniards; The Spanish soon began to refer to her as “Doña Marina”, an honorific sign of respect.

To the indigenous people he became Malintzin, a phonetic translation of the Christian name. To the Spaniards, this looked like Malinche.

Detailed view of the mural “Cortés y La Malinche” by José Clemente Orozco.

Historians say that as the invaders moved north, Malinche tried to persuade Native groups to surrender or face destruction.

“When the Spanish approached a town, he would tell people: ‘You can join the Spanish and help bring down the Aztecs. Or you can fight the Spanish,’ said Camilla Townsend, a Rutgers University historian who wrote an acclaimed biography of Malinche. “‘But in the long run, they will win.’ ”

He was, in a sense, both diplomat and spy at the same time. The Spanish trusted him because he plotted against them and helped recruit Native warriors to Cortés’ side.

“He saved the lives of the Spanish many times,” Camba Ludlow said.

Illustrations from the period show Malinche as an important figure, serving as translator during Cortés’ groundbreaking meeting with Moctezuma at a causeway leading to Tenochtitlán on 8 November 1519.

After the defeat of the Aztecs in 1521, Malinche married Juan Jaramillo, one of Cortés’ captains, and they had a daughter, María.

The former slave girl became a noblewoman in New Spain, but she did not have much time to enjoy her exalted status. By 1529 he was dead, probably succumbing to smallpox, a scourge of Europe.

There is no record of where he was buried. Its remains may lie somewhere beneath the present-day urban chaos of Mexico City.

For many young Mexicans, Malinche’s so-called curse seems like a distant concern, a flashback to another generation, another Mexico. In 2024, the country elected its first female president, Sheinbaum, and anger over femicide, the killing of women because of their gender, is growing.

With Mexico shedding its legacy of machismo, it’s perhaps not all that surprising that a statue of Malinche stands in the capital.

View of the feet of the new statue of La Malinche, originally known as Malintzin, along Paseo de la Reforma in Mexico City.

“It is time for Mexican women and the indigenous people of Mexico to be freed from the burden of this kind of metaphorical ancestor, La Malinche, who has long been portrayed as such a terrible person,” Townsend said. “The real woman was brave and smart. And she coped with the most difficult circumstances as well as humanly possible.”

But Cortés remains a despised figure. There is no statue of him.

Special correspondent Cecilia Sánchez Vidal contributed to this report.