Sperm from donor with cancer-causing gene was used to conceive almost 200 children

James GallagherHealth and science reporter

Shutterstock

ShutterstockA sperm donor who unknowingly had a genetic mutation that significantly increases the risk of cancer fathered at least 197 children across Europe, a major investigation has found.

Some children have already died, and only a small minority who inherit the mutation will be cancer-free in their lifetime.

The sperm was not sold to clinics in the UK, but the BBC confirmed that a “very small” number of British families reported to it had used donor sperm while undergoing fertility treatment in Denmark.

Denmark’s European Sperm Bank, which sells the sperm, said it expressed its “deepest sympathies” to the affected families and acknowledged that the sperm was being used to make too many babies in some countries.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe investigation was carried out by 14 public broadcasters, including the BBC, as part of the European Broadcasting Union’s Investigative Journalism Network.

The sperm came from an anonymous man who was paid to donate money while he was a student, starting in 2005. His sperm was later used by women for about 17 years.

He is healthy and has passed donor screening checks. But the DNA in some of his cells mutated before he was born.

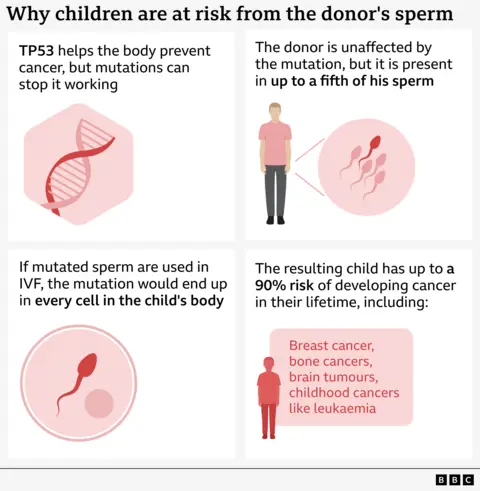

It damaged the TP53 gene, which has a critical role in preventing body cells from turning into cancer.

Most of the donor’s body does not contain the dangerous form of TP53, but up to 20% of his sperm contains this dangerous form.

However, any child made from affected sperm will have the mutation in every cell of their body.

This is known as Li Fraumeni syndrome and increases the risk of developing cancer, particularly in childhood, and breast cancer later in life, up to 90%.

“This is a terrible diagnosis,” cancer geneticist Prof Clare Turnbull, from the Institute of Cancer Research in London, told the BBC. “It’s very challenging to diagnose a family, there’s a burden that comes with living with that risk for life, it’s obviously devastating.”

MRI scans of the body and brain, as well as abdominal ultrasounds, are needed every year to detect tumors. Women often choose to have their breasts removed to reduce their risk of cancer.

The European Sperm Bank said that “the donor himself and his family members were not ill” and that such a mutation “could not be detected preventively by genetic screening.” They said the donor was “immediately blocked” when problems were discovered with his sperm.

children died

Doctors who care for children with cancer linked to sperm donation voiced their concerns at the European Society of Human Genetics this year.

They reported finding this variant in 23 of the 67 children known at the time. Ten people had already been diagnosed with cancer.

Thanks to Freedom of Information requests and interviews with doctors and patients, we are able to reveal that significantly more children are born from donors.

The figure is at least 197 children, but this may not be the final number as data is not available from all countries.

It is also unknown how many of these children inherited the dangerous variant.

Cancer geneticist Dr. from Rouen University Hospital in France presented the first data. Edwige Kasper explained the research as follows: “We already have many children with cancer.

“We already have some children with two different cancers, and some of them have already died at a very young age.”

Céline (not her real name) is a single mother in France whose child was born 14 years ago with donor sperm and was mutated.

She received a call from the fertility clinic she used in Belgium asking for her daughter to be screened.

He says he has “absolutely no resentment” towards the donor, but that it is unacceptable for him to be given “unclean, unsafe and risky” sperm.

And he knows cancer will loom over them for the rest of their lives.

“We don’t know when, we don’t know which one, and we don’t know how many,” he says.

“I understand that there is a high probability of this happening, and when it does, we will fight, and if there are several, we will fight several times.”

The donor’s sperm was used by 67 fertility clinics in 14 countries.

The sperm was not sold to clinics in the UK.

But as a result of that investigation, authorities in Denmark told the UK’s Human Fertilization and Embryology Agency (HFEA) on Tuesday that British women were traveling to the country to receive fertility treatment using donor sperm.

These women were informed.

Peter Thompson, chief executive of the HFEA, said a “very small number” of women were affected and “were informed of the identity of the donor by the Danish clinic where they were treated”.

We do not know whether any British women have received treatment in other countries where donor sperm has been distributed.

Concerned parents are advised to contact the clinic they use and the fertility authority in that country.

The BBC chooses not to disclose the donor’s identification number, stating that the donor made the donation in good faith and has been contacted by known cases in the United Kingdom.

There is no law regarding how many times a donor’s sperm can be used worldwide. However, each country determines its own borders.

The European Sperm Bank acknowledged that these limits were “unfortunately” violated in some countries and was “in dialogue with authorities in Denmark and Belgium”.

In Belgium, a single sperm donor only needs to be used by six families. Instead, 38 different women gave birth to 53 children to the donor.

The UK limit is 10 families per donor.

‘You can’t evaluate everything’

Prof Allan Pacey, who once ran the Sheffield Sperm Bank and is now deputy head of the University of Manchester’s School of Biology, Medicine and Health, said countries had become dependent on large international sperm banks and half of the UK’s sperm was now imported.

“We have to import from the big international sperm banks, which also sell to other countries, because that’s how they make their money, and that’s where the problem starts, because there’s no international law on how often you can use sperm,” he told the BBC.

He said the case was “terrifying” for everyone but that it was impossible to make sperm completely safe.

“You can’t screen everything, under the current screening regulation we only accept 1% or 2% of all men who apply to be sperm donors, so if we tighten it up any further we won’t have any sperm donors; that’s where the balance lies.”

This case, along with that of a man who was ordered to give up having fathered 550 children through sperm donation, has renewed questions about whether tighter limits should be in place.

The European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology recently recommended a limit of 50 families per donor.

But he said this would not reduce the risk of developing rare genetic diseases.

On the contrary, it is better for the well-being of children who discover that they are one of hundreds of half-siblings.

“More needs to be done to reduce the number of families born to the same donors around the world,” said Sarah Norcross, director of the Progress Educational Trust, an independent charity for people affected by infertility and genetic conditions.

“We don’t fully understand what the social and psychological consequences of having these hundreds of half-siblings would be. It could be potentially traumatic,” he told BBC News.

The European Sperm Bank said: “Particularly in light of this case, it is important to remember that thousands of women and couples do not have the opportunity to have children without the help of donor sperm.

“If sperm donors are screened according to medical guidelines, it is generally safer to have children with the help of donor sperm.”

But what if you’re considering using a sperm donor?

Sarah Norcross said these cases were “vanishingly rare” considering the number of children born to a sperm donor.

The experts we spoke to all said that using a licensed clinic means sperm is screened for more diseases than most expectant fathers.

Prof Pacey asked: “Is this a donor from the UK or a donor from somewhere else?” He said he would ask.

“If it is a donor from somewhere else, has this donor been used before, or how many times will this donor be used?” I think it is legitimate to ask questions like these.

If you or someone you know has been affected by the issues raised, you can find details of help and support at: BBC Action Line.