Analysing Indian States’ macro-fiscal health

WHen Hen India’s national auditor, auditor and auditor (CAG) issued a decadal analysis of the macro-macro-macro-good health of the states, a title has been said to have traveled faster than anything emphasized in the study-outtar Pradesh, labeled for a long time, labeled for a long time, LA 37,000 Crore.

This number, which is more than twice the excess of Gujarat, was greeted as proof that the most crowded state of India has returned to a corner. However, only focusing on the number, one missed a bigger picture. Only narrowing arithmetic surpluses may limit the analytical interpretation if the form for the governance of a state is not more integrated with operational mechanics and options.

Economists often promote higher capital expenditures for growth while keeping routine costs under control. These figures decide whether the neighborhood hospital has new ventilators; Whether a school received enough teachers; And whether the village roads will be repaired this year. Indian provinces carry out some of the world’s largest budgets – in fact larger than many countries. Cumulatively, due to the distinction between constitutional powers, they spend more than the Union government for health and prosperity. Nevertheless, should states enough to pay their bills? Or are they borrowing?

Unequal income

In the early 2000s, states were often missing and spent much more than they earned. Reforms, better tax collection and growth growth helped to turn the corner until the end of the 2010s and gave several more reports. However, it was a turning point of the pandem – while the emergency expenditures rose, the tax revenues decreased and almost every state pushed back. The picture is mixed today. Although some states may seem comfortable, most of their stability are based on variable sources such as lottery, mining royalties or land sales.

Indian states live in different financial worlds, such as various ethno-dilsal identities. In Maharashtra 2022-23, Arunaçhal Pradesh managed only 9% of his receipts in 2022-23. Despite a surplus, Uttar Pradesh produced only 42% on his own based on union transfers. From an economic point of view, this is called a vertical imbalance – while the rich states finance themselves, the poorer lean on Delhi.

Kerala won approximately 12,000 crore in the Lottery Industry 2022-23; Odisha received 90% of its non -tax income from mining copyrights; And Tahangana sold 9,800 crore land. However, lottery rights for sales, global prices and land cannot be sold twice.

Gross debt debt

Let’s analyze numbers from CAG’s On Decadal Analysis Report. When states spend more than they earn, they tend to borrow more. They finance this deficit with loans or bonds to be repaid with interest. CAG brings us a consolidated national picture through supervised government financing reports, while the RBI’s State Finance: Budget Report Study offers a consistent framework for comparison. Together, these sources show that borrowing patterns between 2016-17 and 2022-23 are sharply separated in India.

Table 1 Andhra Pradesh, Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Bihar, Chhattisgarh and Goa are interested in states. Andhra Pradesh doubled his borrowings to 1.86 Lakh Crore, doubled the Bihar, and the debt made the debt into a routine tool even for the poorer states. In contrast, Goa kept a strict cover on the prominent borrowings as a rare conservative. Nevertheless, the obligation data shows the weight of these options: Andhra Pradesh’s debt burden rose to 35% of the gross state domestic product (GSDP) until 2023, and Bihar was around 39% among the highest of India. Assem’s rapid borrowing was cushioned by growth, while the obligations gently alleviate 22% of the GSDP, while Goa remained at 27%, still high for a small situation.

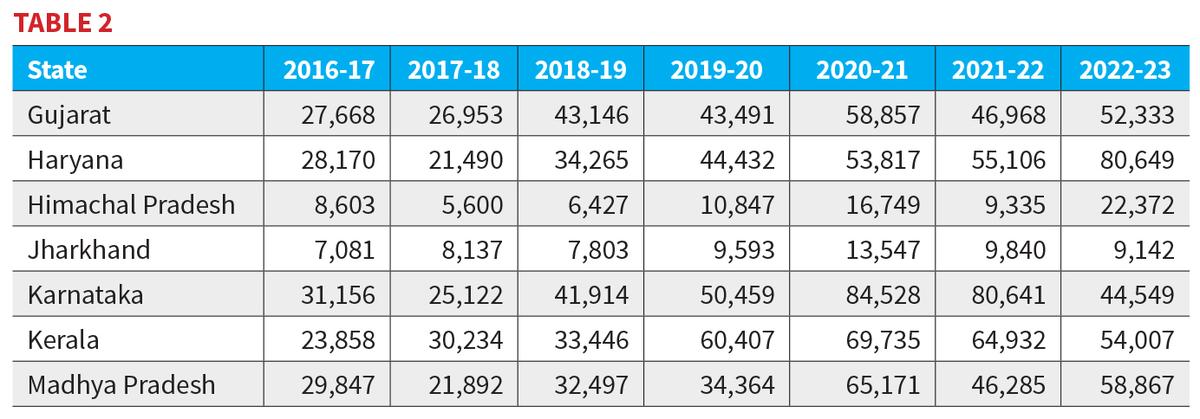

Table 2 Gujarat, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala and Madhya Pradesh are interested. Here, borrowings were measured but permanently rose. In 2016-17, Haryana jumped from 28,170 CRORE to 80,649 Crore in 2022-23, and although it was one of the richer states, it almost doubled their borrowing; His obligations rose to approximately 31% of GSDP. Gujarat gradually moved upwards, rose from 27,668 Crore to 52.333 Crore, while the debt burden kept its debt burden close to 19-20% of the GSDP. Madhya Pradesh also doubled its borrowing from almost two 29.847 Crore to 58,867 Crore and its obligations rose to approximately 29%.

My pande brought volatility. Karnataka’s borrowings rose to 84,828 Crore before returning to 44,549 Crore in 2020-21; Even after re -withdrawal, their obligations stood close to 28% of GSDP. Kerala went to the top of 69.735 Crube and then reached 54.007 Crore, but the debt burden remained stubbornly high, in about 37% of the GSDP. Smaller states remained modest – Himachal Pradesh’s obligations reached approximately 48% of GSDP, while Jharkhand’s borrowings progressed between 7,000 – ₹ 13,500 Crore with a more stable burden of GSDP.

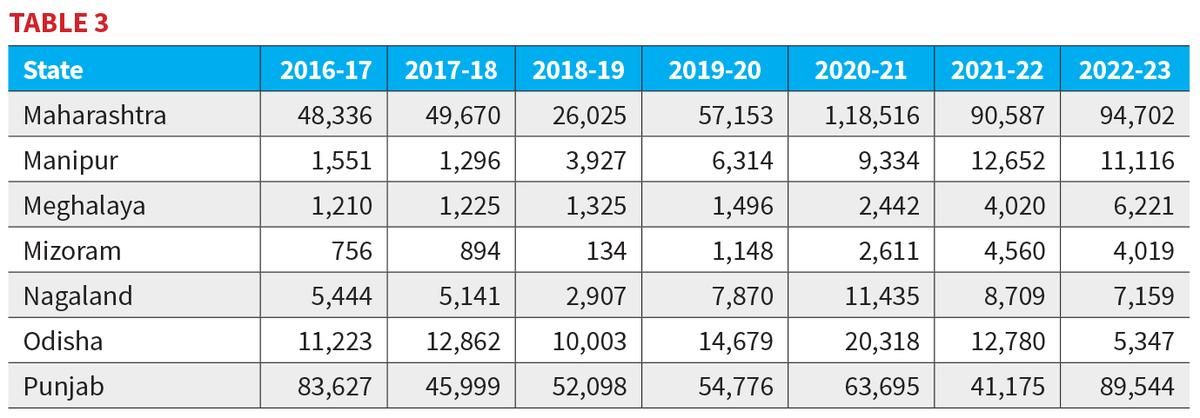

Table 3 Maharashtra, Manipur, Meghala, Mizoram, Nagaland, Odisha and Punjab. This cluster emphasizes excessive ends. Maharashtra borrowings were inflated from the low 26.025 Crore in 2018-19 to the increase in 1,18,516 CRORE in 2020-21, and in 2022-23, 94,702 Crore. However, the major economy kept its debt burden in about 20% of GSDP. Punjab continued to borrows between 83,627 Crore in 2016-17 and 89,544 Crore in 2022-23; Their obligations rose to approximately 45% of the GSDP and showed chronic stress. Thanks to the mining winds, Odisha reduced borrowing from 5,223 Crore to 5,347 Crore, and its obligations fell to about 15% of the lowest GSDP in India.

Manipur’s borrowings rose from 1,551 Crore to 11.116 Crore; From 1,210 CRORE TO 6,221 CRORE TO MEGALAYA; 4,019 Crore from Mizoram La 756 Crore; and Nagaland, 5.444 Crore to 7,159 Crore. Although it is small in absolute numbers, these states carry some of the heaviest loads, obligations vary from approximately 40-60% of the GSDP and indicate increasing financial addiction.

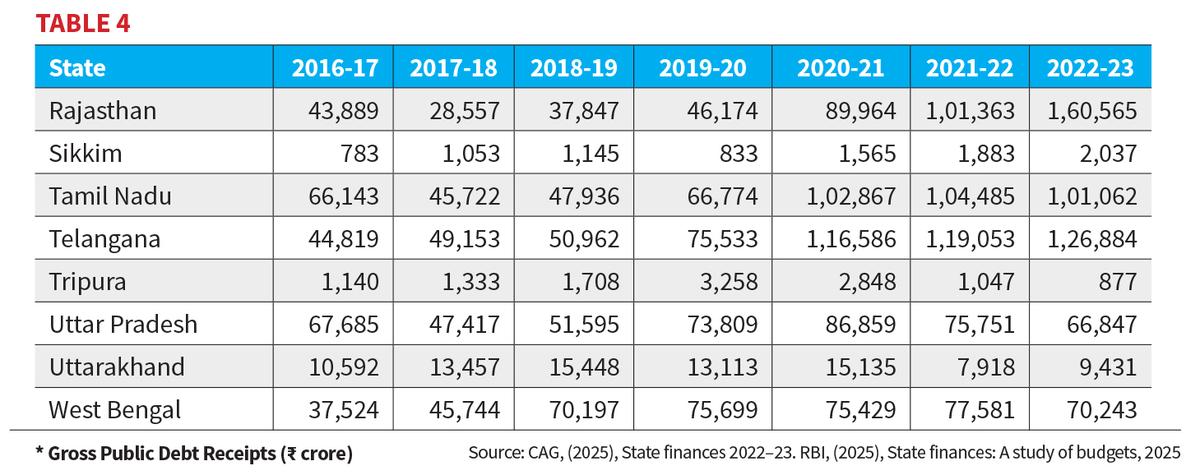

Table 4 Rajasthan exhibits Rajasthan, coin, Tamil Nadu, TaLangana, Tripura, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand and West Bengal. Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu emerged as heavy debtors. In 2016-17, Rajasthan increased his borrowing from 43.889 Crore to 2022-23 to 1,60,565 Crore, one of the most upright climbing throughout the country, and his obligations rose to approximately 40% of the GSDP. Tamil Nadu rose from 66.143 Crore to 1,01.062 Crore, while the debt rate rose to approximately 33%. Tahangana rose from 44.819 Crore to 1,26,884 Crore, but kept strong growth obligations moderate as about 28%.

West Bengal has grown moderately growth from 37,524 CRORE to 70,20,20.243 Crore, and the obligation remained high in 37% of the GSDP. On the other hand, Uttar Pradesh slightly reduced borrowing from 67,685 Crore to 66.847 Crore in 2016-17 and kept its obligations as constant as approximately 31%. Uttarakhand’s borrowings fell from 10.592 Crore to 9.431 Crore, but the obligations were still more than 32% of the GSDP, Tripura La 1.140 Crore fell to only 877 Crore from Crore, but carried a debt burden of over 30%. Although the coin was about 24% of its debt GSDP, it remained marginal under 2,100 crore.

During the pandemi, borrowings increased everywhere. However, what happened later was different: some states such as Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan and Tahangana continued to increase their borrowing; Karnataka, Kerala and Maharashtra were cut back; And a few of them, such as Odisha, Uttar Pradesh and Tripura, have even further reduced their borrowing and revealed very different financial strategies.

Welfare Paradox

While some states show surpluses, they actually delay central transfers, budget -free loans and GST compensation. Most of these states do not spend enough for prosperity priorities and therefore may have accounting gains without any more developmental gains reported. In addition, states such as Punjab are chronic debtor wrestling; Kerala rely on variable revenues from lottery; Andhra Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh see the cost of postponed to opaque warranty machines and special purpose vehicles through free power and farm waves.

Corporate tax deductions, GST stops and social expenditure, masking the real burden of financial cautiousness left a mirage. With the latest GST regime and expected a higher financial income loss, it does not know the wider impact of states on financial expenditures on frugal welfare budgets. Nevertheless, in this fragility, the welfare schemes in some central financing plans have increased: PM-Customer deposits, Ujjwala cylinders and Ayushman Bharat cards, and the face of the prosperous populist base of India, such as deciding and leader.

This tension of a state that generously spends while challenging revenues frames India’s current welfare paradox. The nation built one of the largest welfare states in the world while maintaining one of the finest financial bases among the extreme dependence on borrowings. Paradox reflects a nation -state that reflects an extraordinary promise with a restricted and inhibiting financial capacity, where care is taken to the threshold of financial famine.

Deepanshu Mohan Professor and Dean, Op Jindal Global University (JGU)and Oxford University Guest Professor, LSE and Research Assistant. Geetaali Malhotra and Aditi Lazarus, JGU, Cnes and research analysts contributed to this article.