The child abuse inquiry was meant to move the dial. Three years on, nothing has changed

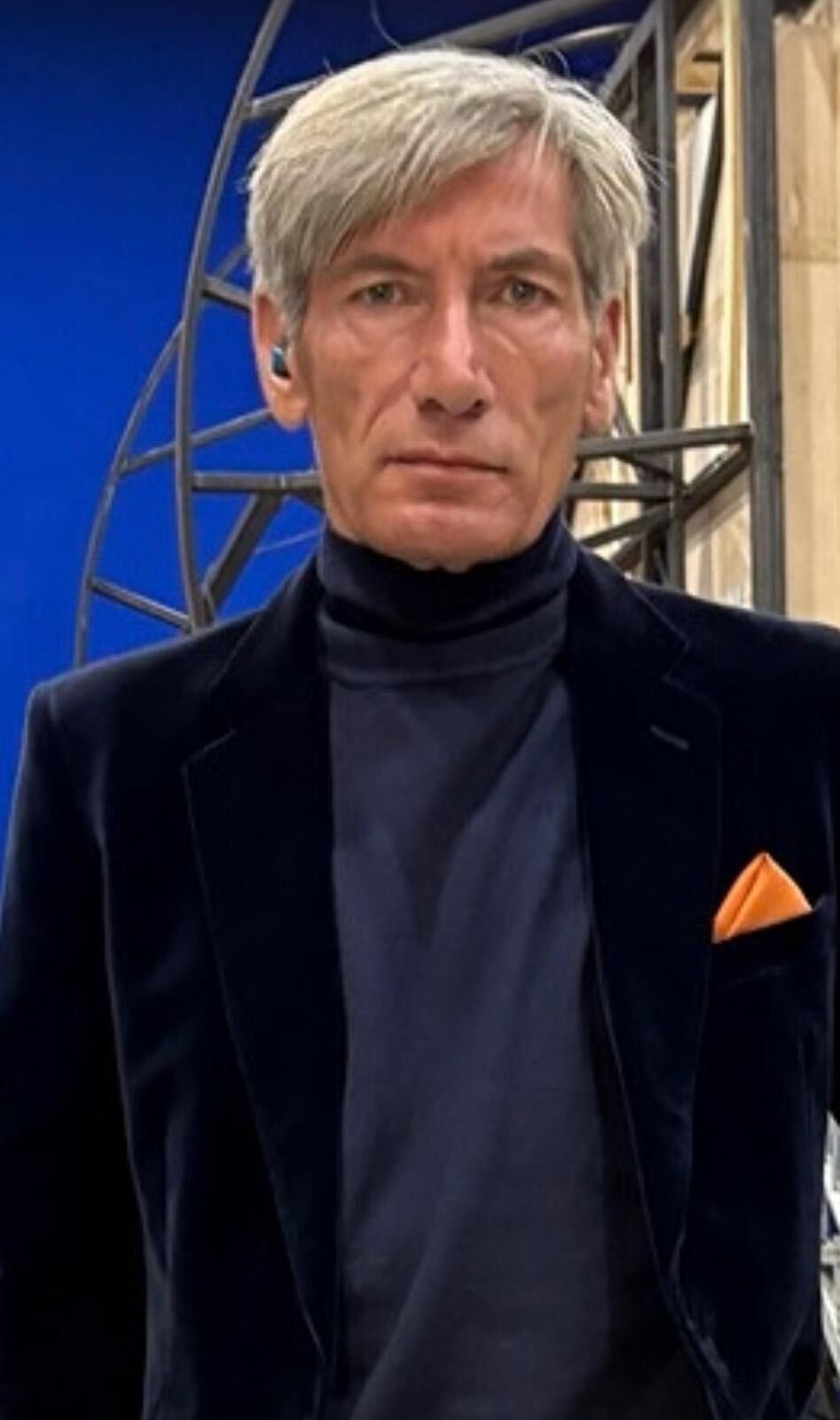

R.Ussell Specterman burst into tears and hung up when her sister called and told her there would be an independent investigation into child sexual abuse.

“I just broke down” he says Independent. “I knew the pain and trauma it would bring out within me.”

Mr Specterman, 59, grew up in the care of Lambeth, the council that became the central case study of the Independent Inquiry (IICSA). The findings would later detail the council’s institutional failings, as it “kept employing adults who posed a risk to children” and “failed to investigate its employees when suspected child sexual abuse”.

It has been more than a decade since the IICSA was first announced after posthumous investigations into the Jimmy Savile scandal revealed widespread child abuse.

It cost a staggering £186.6 million and, over seven years, the investigation involved more than 7,000 survivors. Three different panel chairs were forced to resign before Professor Alexis Jay, who was already a panel member, took office in August 2016.

According to financial reports, panel members were paid a daily wage of £565 for their participation in the investigation. Professor Jay’s predecessor, panel chair Dame Lowell Goddard, was paid an annual salary of £355,000 for the 2015-2016 financial year.

Monday marked the third anniversary of the publication of IICSA’s findings in the final report, which shed light on the institutional nature of child sexual abuse in the country. The report was unhelpfully overshadowed by the resignation of Liz Truss 44 days into her premiership, but it did make 20 key recommendations to protect children.

Three years on, none of the recommendations have been fully implemented and campaigners and survivors are unhappy with the inertia. Another review this year by Baroness Louise Casey called on the government to act on the recommendations.

‘There is no justice’

Mr. Specterman did not give living evidence, but he was a core participant and made a statement; This was something he found difficult to do.

“I struggled to put pen to paper at the best of times, but it was something that had to be done,” he says. “I wanted to help children”

Years later, Mr. Specterman was disappointed that nothing had been done. He thinks “there is no justice” and expresses concern that many of the people involved “made a fortune out of it”.

Looking back on the investigation, Professor Jay says: Independent he was aware of the limits of the kind of justice it could bring.

“A lot of people tend to think that there will be justice from this, but if you consider justice as criminal investigation and prosecution, the public inquiry cannot do that,” he says. “He or she can accurately describe what happened and make suggestions for future improvement.”

“I’ve never had any doubts about the limitations of a public inquiry, but people desperately wanted a public inquiry,” he adds. “I’ve always been clear about this, but you think this is not a court, it’s a quasi-judicial process.”

The lack of implementation of the recommendations is further evidence of a lack of political will for change, according to Professor Julie MacFarlane.

By the time the investigation was launched, Prof MacFarlane, now 67, had moved to Canada and emerged as a survivor of child sexual abuse at the Anglican Church in Chichester. A prestigious legal academic, she sued the Church in 2015, the same year the investigation began, and police went on to successfully prosecute the church’s priest, who sexually assaulted her over 15 months as a teenager.

Already used to talking about her experience, she traveled from Canada to the UK in 2018 specifically to give evidence to the inquiry.

“I had a certain amount of practice by then,” he says. “I wasn’t really afraid to tell that story; I was ready to tell it. It seemed important to tell it, especially when I realized it was going to focus on Chichester and I was going to find out all these things I had no idea about… It made sense for him to do it.” [the minister] I was doing this in a community where this behavior is incredibly tolerated.”

The investigation found that 20 people linked to the Diocese of Chichester over more than 50 years were convicted or pleaded guilty to child sexual offences. The diocese’s “neglect of the physical and spiritual well-being of children and youth was inconsistent with the Church’s mission of love and care,” according to the report.

“I felt like it was my responsibility. It would be easier for me to give the actual testimony than it would be for someone who was doing it for the first time or who wasn’t familiar with giving that kind of presentation,” he adds. “This could help other people do this.”

Prof Macfarlane recalls sitting in front of the panel and being questioned “not very hopeful about what the outcome would be”.

“I wanted them to ask me more questions, and sometimes what I tried to do in my answers was go further than what they were asking in the question,” he recalls. “I felt like they didn’t quite understand… the vulnerability of people, especially young people… to the fact that the power of the church is a very hierarchical institution, and if you’re a believer, then you believe that this person is on God’s side in your life.

“This was an accident waiting to happen when you put someone God has empowered in a situation with young people.”

‘A plan for change’

Prof Macfarlane thinks the key recommendations do not go far enough. One key change that could help victims is removing the authority to investigate allegations of abuse from the church’s brief.

“What the recommendations do is identify better processes, more training etc,” he explains, adding that it would take 15 minutes to expand the category of trusted person to include clergy in the Sexual Offenses Act.

“Given how simple this is and sometimes the legislation is more complex than that, [it’s clear] “I think there is no real political will to do anything about this.”

Considering that approximately 500,000 children are sexually abused each year and less than one in five disclose their abuse. Campaign group ACT at IICSA He went on to emphasize that the government was not acting on what he called “a clear plan for change”.

Professor Jay warned that if the latest 20 recommendations are not met and fully implemented within a certain time frame, the future for children will be extremely bleak.

“In 10 years’ time people will be saying the same things and children will still be sexually abused in the most horrific ways,” she says. “I’m concerned that internet use is increasing internationally and domestically, leading to online abuse. And the speed at which this is changing and worsening is serious.”

Lucy Duckworth, policy lead at the Survivor’s Trust, said: “The importance of Baroness Louise Casey’s report was that IICSA would be completed and that is really clear throughout.

“We absolutely need to look at cases of child sexual abuse, such as grooming gangs, abuse in boarding schools and cover-ups by social service agencies.

“There are so many different places where this happens, and each comes with its own complexities, nuances, and certainly cover-ups.

“But our main goal right now is that all child sexual abuse needs to stop, and we’re not even at a point where we understand how widespread it is. That’s what IICSA is for.”

Safeguarding Minister Jess Phillips said: “Baroness Casey’s report has revealed the unimaginable horrors experienced by some of the most vulnerable people in this country, and how victims and survivors were failed. This will remain one of the darkest moments in our country’s history.”

“Earlier this year, I set out how we would take action on the recommendations made by Alexis Jay’s inquiry to root out failure wherever it occurs. This includes creating a mandatory duty to report child sexual abuse, establishing a new Child Protection Agency for England that will make the safety of our children a priority, and making it easier for victims and survivors to bring claims in the civil courts.

“But more needs to be done, which is why we are launching a new statutory inquiry into reforming gangs to direct and supervise local investigations. In parallel, police have launched a new national operation overseen by the National Crime Agency, which has already flagged more than 1,200 closed cases for review. This will open the door to further convictions, leaving no place to hide for those who exploit the most vulnerable.”

If you are a child and need help because something has happened to you, you can call Childline free on 0800 1111. You can also call the NSPCC if you are an adult and are worried about a child: 0808 800 5000. The National Association of People Abused in Childhood (Napac) offers support to adults with: 0808 801 0331