Stress tests and drones: the new playbook to protect the endangered western hoolock gibbon

At the Hollongapar Gibbon Sanctuary in Jorhat, Assam, the endangered western hoolock gibbon, the only non-human monkey species in India, vie to be heard amidst the thunderous roar of a passenger train passing through the protected forest.

As we walk through the 2,100-hectare sanctuary, visitors listen intently to the cacophonous sounds of gibbon coming from the upper dome as our guide points to a tall hollong tree for which this forest is famous and from which it takes its name.

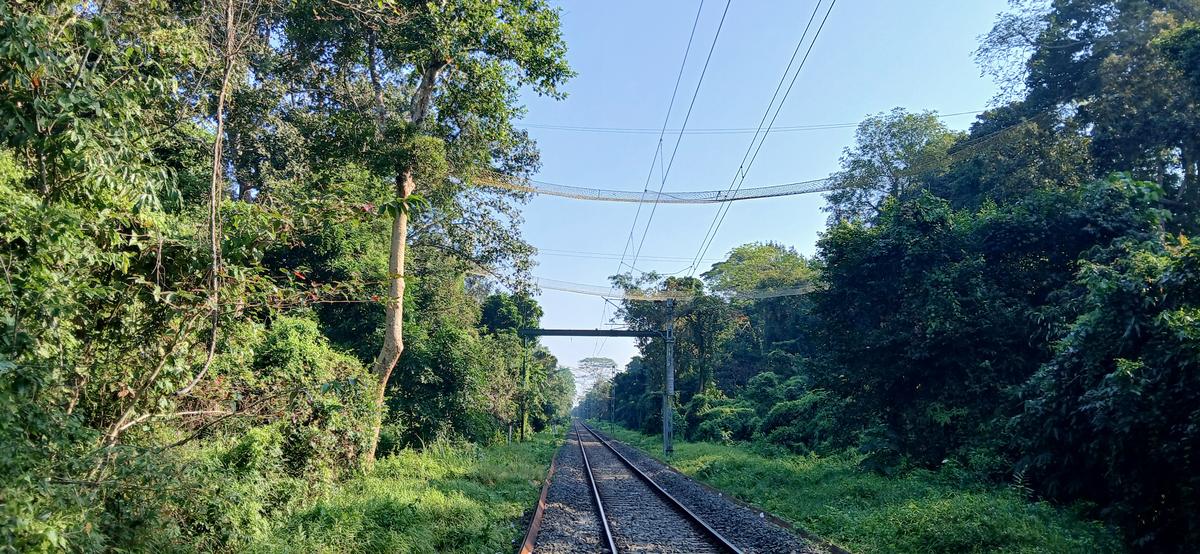

Shortly after, we hear a rustle as a family of gibbons, including two cubs, swing majestically overhead. Even as we watch in amazement, a faint, more threatening rumble grows louder. Gibbons scurry among the trees and the whole forest rings with the deafening noise of a train on the British-era Northeast Frontier Railway line, which divides the forest into two unequal parts.

Tren is typical of the multiple anthropogenic pressures, including habitat loss, fragmentation and hunting, that affect the western hoolock gibbon throughout its range in the northeastern Indian states of Assam, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Nagaland and Mizoram. There has been such a decline over the last half-century that the gibbon’s population has fallen from an estimated 100,000 to less than 5,000.

Rope bridges were installed to facilitate the passage of the gibbon over the North-East Frontier Railway line. To date, no gibbons have been recorded using them. | Photo Credit: Special Editing

Easy target for hunters

Like most of its geographical range, the existence of the gibbon in Assam has been severely restricted by habitat loss and fragmentation. Additionally, threats such as hunting have led to this species becoming one of the most endangered primates in the world. Researchers say the expansion of settled agriculture and deforestation are also destroying the gibbon’s range.

Divya Vasudev, Co-Founder and Senior Scientist at Conservation Initiatives, a Shillong-based non-profit organization, says that although experts believe that 9 out of 10 gibbons have disappeared in the last few decades, an accurate census is difficult to come by. Gibbons are also secondary targets for predators due to their loud calls that can last up to 30 minutes.

Rushikesh Chavan, Director of Noida-based The Habitats Trust, says the challenges faced by gibbons are emblematic of the pressure on low-lying rainforests in Northeast India. Chavan, changing land use and joom cultivation are the main threats to the species. “Previously, these slash-and-burn cycles, where forests were destroyed and then allowed to regenerate, lasted decades. But due to pressures on local communities, these cycles have now shrunk from decades to just 7-10 years,” he says.

Habitat loss, fragmentation and hunting are among the threats affecting the western holock gibbon population throughout its range in Northeast India. | Photo Credit: Getty Images

Studying genetics and stress

Despite the difficulties, attempts are being made to protect the gibbon. Udayan Borthakur, Director and Head of Wildlife Genetics Laboratory (WGL) of Aaranyak, a conservation NGO in Guwahati, says gibbon populations have become “small and isolated” across their entire range. “We are trying to study the source populations that may be in the Garo hills, Dehing Patkai and even Hollongapar.”

Aaranyak is compiling genetic data on gibbon populations through fecal matter collected from forests to understand whether inbreeding and reproductive depression are a concern. “Through these analyses, we are trying to identify source populations. In Hollongapar, for example, our research will show whether the current population increased from a smaller population of a few individuals or whether it came from a larger pre-existing population,” he said.

WGL is also examining stress levels in gibbon populations in different regions to understand whether hormones such as cortisol are higher in populations closer to human settlements and other anthropogenic pressures.

Udayan Borthakur (left) from the Wildlife Genetics Laboratory in Aaranyak, Guwahati, and Santhosh Pavagada from The Habitats Trust keep watch on western holock gibbons in Jorhat, Assam. | Photo Credit: Special Editing

Technology based solutions

Habitats Trust (THT), together with Conservation Initiatives, is working on technology-based solutions to detect gibbons in any habitat. “One of the key challenges researchers face, especially with arboreal species such as gibbons, is that traditional methods such as camera traps used to estimate the population are not applicable as the animals are almost always found in the upper canopy,” says Santhosh Pavagada, THT Conservation Technology Program Leader.

This situation necessitates the use of alternative approaches such as bioacoustics. Machine learning models are being developed to detect gibbon vocalizations from recording devices placed in forests. “The model will assist researchers by extracting gibbon sounds and providing timestamps to quickly navigate to areas of interest in each audio file where a potential gibbon was heard,” says Kishore P., co-director of THT.

Thermal drones are also being investigated for the possibility of detecting gibbons in a landscape using a computer vision model. “This model can analyze 20-40 minutes of flight time, analyze the images and identify gibbons,” says Pavagada.

With some help from the community

Local communities are also involved in species conservation. “Since much of the gibbon habitat in the hill regions of Northeast India is owned and managed by resident populations, it is imperative for these communities to participate in conservation efforts,” says Varun Goswami, Co-Founder and Senior Scientist at Conservation Initiatives.

Vasudev says there are more than a hundred tribes, each with their own unique laws and traditions regarding forest protection and hunting. “Some tribes ban the hunting of gibbons, but we need to bring more on board to ensure the protection of the species,” he adds. “The more villages we work with and the more people show conservation support and ensure that some forest is safe on their land, the better. The real driving force needs to come from the community.”

rohan.prem@thehindu.co.in

It was published – 24 December 2025 17:43 IST