Thousands of Chinese lured abroad and forced to be scammers

CCTV

CCTV“Should I feel anything?” asks the beady-eyed man sitting in a padded cell, his wrists cuffed.

He is being interrogated by Chinese investigators for allegedly ordering a human offering to be made to a foreigner to celebrate his sworn brotherhood with a business partner.

“Wasn’t he a living, breathing human being?” a researcher asks.

“I didn’t feel much of anything,” the man continues.

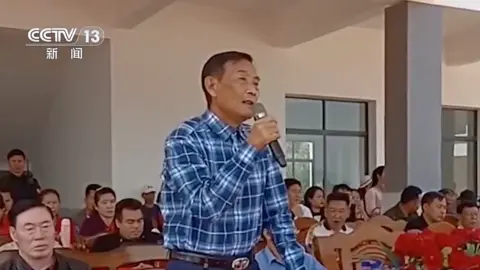

The scene may sound like something straight out of a crime drama. In fact, this is part of a documentary on Chinese state media; is an almost unheard of look at the workings of the justice system in a country where court proceedings are largely kept out of public view.

The handcuffed man answering questions is Chen Dawei, a member of the infamous Wei family, one of several powerful mafia groups that have operated untouched for years in Myanmar’s border town of Laukkaing.

His confession is just one part of a months-long propaganda effort by Chinese officials. It both warns the Chinese public about South East Asia’s billion-dollar fraud industry and highlights the Chinese government’s crackdown on the men behind an industry that has ensnared thousands of people and stolen billions of dollars.

As one researcher put it, the message China wants to send is clear: “This is to warn other people, no matter who you are, no matter where you are, as long as you commit such heinous crimes against the Chinese people, you will pay the price.”

Or to use a Chinese saying: Kill the chicken to scare the monkey.

pay the price

There are few hens as big as the Weis, Lius, Mings and Bais (godfather-like families) who came to power in Laukkaing in the early 2000s.

Under their rule, the impoverished backwater was transformed into a glitzy hub of casinos and red-light districts.

Newer are scam farms that hold people against their will, forcing them to defraud strangers online and subjecting them to cruel punishments and even death. Most of those trapped were Chinese and were targeting people in China.

But in 2023, the families’ empires collapsed when Myanmar authorities arrested them and handed them over to China. Chinese courts have since tried them for crimes ranging from fraud to human trafficking to murder.

CCTV

CCTVNow examples are being made of families: 11 members of the Ming clan and five members of the Bais were sentenced to death, while dozens were given long prison sentences. The case against the Lius and Weis is ongoing.

From the shine of the handcuffs to the color of the prison uniforms, their descent into disgrace is clearly visible in the documentaries they show.

It’s a far cry from the lives they lived just two years ago.

The rise of fraudster clans in Myanmar

Laukkaing’s godfathers came to power after Min Aung Hlaing, who now heads Myanmar’s military government, led an operation to oust the town’s then-dominant warlord.

The military leader was looking for collaborating allies, and Bai Suocheng, then the warlord’s deputy, fit the bill.

According to Chinese media reports, Bai was appointed head of the Laukkaing region and his family came to command a 2,000-strong militia force.

A handful of families intervened in the power vacuum left by these changes and secured military and political power.

According to Chinese investigators, the Wei family included a member of parliament and a military camp commander. Meanwhile, the Lius controlled basic infrastructure such as water and electricity and had strong influence over local security forces.

CCTV

CCTVThey earned money by gambling and prostitution for years.

But lately they have also expanded into cyber fraud operations, with each family controlling dozens of scam compounds and casinos raking in billions of dollars.

While families live large lives with grand banquets and luxury cars, a disgusting culture of violence thrives behind the walls of fraud compounds, Chinese officials said.

Testimonies collected from released workers indicate widespread abuse: fingers cut with knives, hitting with electric batons and regular beatings. Uncooperative workers were locked in small dark rooms and starved or beaten until they gave up.

China’s war against ‘fraud’

Many Chinese workers were drawn there by lucrative job offers, no doubt attractive in an environment of China’s economic slowdown and high youth unemployment.

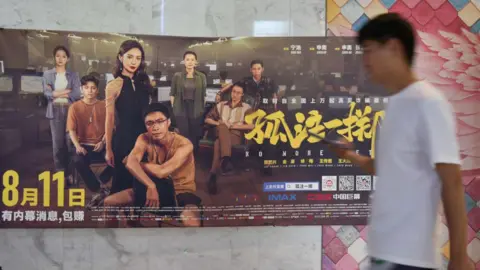

Horror stories of such scam hubs have infiltrated everyday conversations in China, from taxi rides to social media and popular culture.

No More Bets, the 2023 blockbuster about Chinese people smuggled into a foreign scam farm, has kept millions of Chinese tourists away from Thailand, which has gained a reputation as a hub for scams in Myanmar and Cambodia.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn January this year, national attention was on junior Chinese actor Wang Xing, who flew to Thailand for an acting job but was taken to a fraud center on the Myanmar border.

His family’s search for him went viral and he was eventually rescued.

But Wang is in the lucky few. Many Chinese are still searching for lost loved ones in Southeast Asia’s fraud hotspots.

“My cousin was brought there four or five years ago. We have never heard from him. My aunt is in tears every day, it is difficult to describe her current situation,” one Weibo user wrote last month.

Selina Ho, an associate professor at the National University of Singapore who specializes in Chinese politics, told the BBC that “by announcing the latest crackdown, Chinese authorities aim to calm domestic emotions and reassure victims’ families.”

EPA-EFE/REX/Shutterstock

EPA-EFE/REX/ShutterstockThe UN estimates that hundreds of thousands of people are still trapped in fraud hotspots around the world.

To Beijing’s chagrin, those operating such fraud centers are mostly Chinese.

This is common knowledge among Chinese citizens. “When you go abroad, the people you should least trust are your own citizens,” reads one comment on Weibo.

“The fact that Chinese citizens are the brains behind many of these operations is deeply damaging to China’s image on the international stage,” Ivan Franceschini, co-author of Scam: Inside Southeast Asia’s Cybercrime Compounds, told the BBC.

As concerns grow in the country, Chinese authorities are eager to demonstrate their commitment to dismantling these massive fraud networks.

China and Myanmar authorities have arrested more than 57,000 Chinese citizens for their role in cyber fraud since 2023, state media reported.

CCTV

CCTVAnd they made it clear that it wasn’t just the Dads they were after.

In October, China announced a lawsuit against another syndicate in Laukkaing, which they described as a “new generation of power” and “no less violent” than the notorious families.

In yet another state media documentary, a Chinese official investigating this union recalled what his team leader had told him: “If this case is not solved, it will be a permanent stain on your career.”

Despite China’s best efforts to crack down and the publicity that follows, the numbers offer some optimism: Reported cases of cyber fraud in China have steadily declined over the past year, and officials say such crimes have been “effectively prevented.”

As one official told documentary viewers, investigating fraudulent gangs in Myanmar made him realize “how happy we are in China and how important the sense of security is to the Chinese people.”

Additional reporting by Kelly Ng