Trump’s move to topple Maduro is fraught with risk

Ione WellsSouth America correspondent

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe United States may want many of its enemies to fall from power. He usually doesn’t send in the army and physically eliminate them.

Venezuela’s sudden awakening came in two ways.

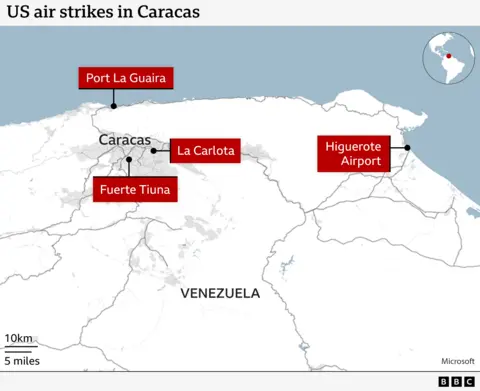

Residents were suddenly awakened by deafening explosions: the sound of the capital, Caracas, under attack from US strikes targeting military infrastructure.

His government has now awakened from the illusion that US military intervention or regime change is only a distant threat.

US President Donald Trump announced that leader Nicolás Maduro was captured and sent out of the country. He now faces trial in the United States on weapons and drug charges.

The United States has not intervened directly in Latin America in this way since it invaded Panama in 1989 and overthrew then-military ruler Manuel Noriega.

Then, as now, Washington framed it as part of a broader crackdown on drug trafficking and criminality.

The United States has long accused Maduro of leading a criminal trafficking organization, which Maduro vehemently denies. It designated the ‘Cartel de los Soles’ (the name used by the US to describe a group of elites in Venezuela who it claimed were organizing illegal activities such as drug trafficking and illegal mining) as a foreign terrorist group.

Maduro’s government has been accused of human rights violations for years.

In 2020, United Nations investigators said his government had committed “serious violations” amounting to crimes against humanity, such as extrajudicial killings, torture, violence and disappearances, and that Maduro and other senior officials were implicated.

Human rights organizations noted that there were hundreds of political prisoners in the country; some of them were detained following anti-government protests.

This latest operation, attacking directly inside a sovereign capital, marks a dramatic escalation of US involvement in the region.

Maduro’s forced removal will be hailed as a major victory by some hawkish figures within the US administration; many of them argued that only direct intervention could remove Maduro from power.

Washington does not recognize him as the country’s president since the 2024 elections. The opposition released electronic voting tallies after the vote proving that Maduro, not Maduro, won the election.

The result was deemed neither free nor fair by international election observers. Opposition leader Maria Corina Machado was banned from participating in the contest.

But for the Venezuelan government, this intervention confirms what it has long claimed: that Washington’s ultimate goal is regime change.

Venezuela also accused the United States of wanting to “steal” its oil reserves, the world’s largest, and other resources; He felt this claim was confirmed after the US seized at least two oil tankers off the coast.

The attacks and captures took place after months of US military tension in the region.

The United States has sent its largest military deployment to the region in decades, including warplanes, thousands of soldiers, helicopters and the world’s largest warship. It has launched dozens of attacks on ships allegedly smuggling small drugs in the Caribbean and Eastern Pacific, killing at least 110 people.

Any remaining doubts that these operations were at least partly about regime change have now been dispelled by today’s actions.

What remains extremely unclear is what happens next within Venezuela itself.

The United States clearly wants the Venezuelan opposition, with which it is allied, to come to power, possibly led by Nobel Peace Prize-winning opposition leader Maria Corina Machado or opposition candidate Edmundo Gonzalez in the 2024 elections.

But even some critics of Maduro warn that this will not be easy, given the government’s grip on power in the country.

It controls the judiciary, the Supreme Court and the military, and is allied with powerfully armed paramilitary forces known as “colectivos”.

AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesSome fear US intervention could trigger violent disintegration and a protracted power struggle. Even some who dislike Maduro and want him gone are wary of instrumental US intervention, remembering decades of US-backed coups and regime changes in Latin America in the 20th century.

The opposition itself is also segmented; Not all of them support the switch to Machado or his support for Trump.

It is unclear what the US’s next move will be.

Will he try to pressure for new elections? Will he try to remove higher-ranking members of the government or military and force them to face justice in the United States?

As for Trump, his administration has become increasingly powerful in the region, with a financial bailout for Argentina, tariffs on Brazil to influence the coup trial of Trump ally and Brazil’s former right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro, and now military intervention in Venezuela.

Ecuador now benefits from having more allies in the region, with the continent shifting to the right in recent elections, as in Argentina and Chile. However, although Maduro has few allies in the region, there are still major powers such as Brazil and Colombia that do not support US military intervention.

And some of Trump’s MAGA base in the US are also unhappy with his increased interventionism after promising “America First”.

For Maduro’s closest allies, Saturday’s events raise urgent questions and fears about their own futures.

Many people may not want to give up the struggle or allow a transition unless they feel that they can receive some kind of protection or reassurance in the face of persecution.